Insight Paper March 27, 2019

Banking Embraces Smart Regulatory

Federal Reserve introduces stronger tiered approach in regulatory and earnings reporting cadence adjustments.

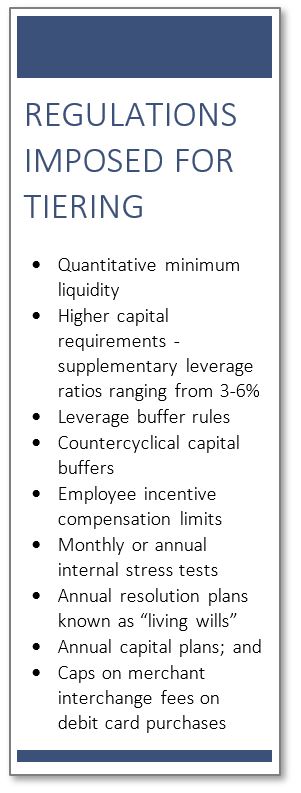

On the last day of October 2018, the Federal Reserve solicited public comments for its approach towards lessening regulatory and compliance standards among the largest financial institutions. PNC Financial, Charles Schwab, U.S. Bancorp, and Capital One are just a few examples of the institutions that will profit from a new regulatory approach that more closely aligns with the banks’ documented risk factor. “The proposals would prescribe materially less stringent requirements on firms with less risk, while maintaining the most stringent requirements for firms that pose the greatest risks to the financial system and our economy,” Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome H. Powell, remarked.1 Institutions deemed to have the lowest risk and a consolidated asset portfolio of $100 to $250B would forego complying with standardized liquidity requirements. However, they would remain exposed to stress test standards set forth after the 2008 crash, with the knowledge that these tests will now exist in parallel and on a two-year cycle, instead of annually. For institutions with $250B or more on the books, they will still be required to engage in company-wide stress tests but will also move to the two-year cycle (abandoning their semi-annual requirements). Additionally, standardized liquidity requirements will still be required, unlike sub $250B banks, but the guidelines will be lessened.

It’s important to magnify that, while this is a proposed massive deregulation effort by the current Fed, banks that sit within the highest risk categories will be unqualified to benefit from this shift. Current regulations will continue to stand. The introduction of a tiering system has been talked about for years. In 2014, Daniel Tarullo, a member of the Fed board, gave a speech in Chicago on the advantages of a tiered regulatory approach towards banks. Tarullo stated, “This approach is what we now characterize as microprudential – that is, the focus is on the soundness of individual banks rather than on the financial system more broadly.” Besides the massive financial effect this will have on soothing overhead and compliance spending amongst banking institutions that fit in the lesser risk categories, this approach carries the possibility of unleashing a swath of M&A activity. For a decade now, mid-tier banks have suffered under overbearing regulatory constraints and burdens. A tiered regulatory approach would open the door for middle of the pack banks to take on additional risk and participate in M&A activity.2 If the policy is formally implemented in time and not manipulated or overturned during a new political administration, this addition (or alteration) to the Economic Growth, Regulatory Reform, and Consumer Protection Act will usher in a calming of regulatory criteria.

Whether it’s a calming of the storm to come or a fresher outlook on a private sector/public sector partnership, regulatory has been going through some immense changes over the past few years. Two months before Tarullo’s speech, the current U.S. administration began visiting the concept of rethinking reporting quarterly earnings and moving to a more efficient model of twice a year or every six months.3

The SEC has been engaged by The President to investigate this possible change and analyze potential benefits. Quarterly reporting has been the norm since the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which mandated quarterly 10-Q reports in each of a company’s first three fiscal quarters and a more intensive 10-K report at the end of the fiscal year. Very small public companies can file an accelerated form, but the limit is so low – $700M in public float – that essentially every U.S. public company files similarly. A separate filing on form 8-K is required whenever there is a material change in a company’s business in between quarterly filings.4 Some institutions have perpetuated that this rush to release earnings has created a culture of trigger finger trading and inaccurate (or incomplete) company public statements. In some cases, it has often been suggested that CEOs and banking leadership are encouraged to focus on short-term wins rather than sustainable, long-term growth or opportunity. While this potential earnings call scheduling change is not limited to the banking sector, financial services seems to be the primary champion for the change and will be a main source of impact if the tradition is revisited.

What do these two [tiering and earnings cadence] introductions to regulatory bring to the table? First and most importantly, it provides many banks and corporations an opportunity to enact cost-saving measurements. Institutions will no longer require the workforce to churn out earnings research and submit filings every three months but, instead, will be able to expend more effort on obtaining and reporting accurate, trading-executable information on a twice-per-year basis. In the case of tiering, mid-level institutions will not be restricted or have to employ a significant work burden to manage and respond in accordance with certain tiering parameters. This would free up overhead cost and, similar to what we noted before, allow banks to finally reenter the M&A market and invest with risk.In both approaches, there are always drawbacks, as well. For example, long-term investors having the most complete set of information possible at all times is critical to making wiser investment and fiduciary decisions. Less frequent reporting would likely benefit those with better connections, to the detriment of the investing public. It’s fairly undeniable that short-term day traders are constantly seeking ephemeral profits in the rapid buying and selling of shares, especially around earnings announcements. This activity exaggerates price swings – which is undoubtedly frustrating for company management – but in the end, it’s just “noise”. Smart long-term investors should avoid hitting the “buy” and “sell” button at the exact moment a company reports results that are a few cents above or below expectations and concentrate instead on what the entire presentation says about the company’s prospects for delivering earnings growth over the coming months and years. Television news tends to focus immediately on the revenue and net earnings numbers as soon as they are released, but there’s generally a lot more information to be gained in the investor presentation and conference calls that come later.5

Tiering has the burden of being one of many public-sector growth taxes on banking. While many advocate for deregulation, there are considerable influencers who see the potential destructive power of a revisit to the strict frameworks and rules the government has imposed to reign in risk. Many believe there is a potential for a resurgence echo of the 2008 financial crisis or the closing of “too big to fail” institutions, such as Lehman Brothers.

Banks provide valuable credit and liquidity services to households and businesses. The banking industry is a large, complex, and integral component of the local, national, and global economies. Regulation is required in order to limit unnecessary risk associated with short-term strategies. With such a wide variance between the size, structure, and practices of various banking institutions, a one size fits all approach is not practical. Thus, tiered regulation makes sense in theory, but the question really becomes exactly how are tiers defined (i.e., is size truly representative of risk?), and what is the level of regulation at each tier that will actually achieve the goals of risk reduction without discouraging healthy growth?6

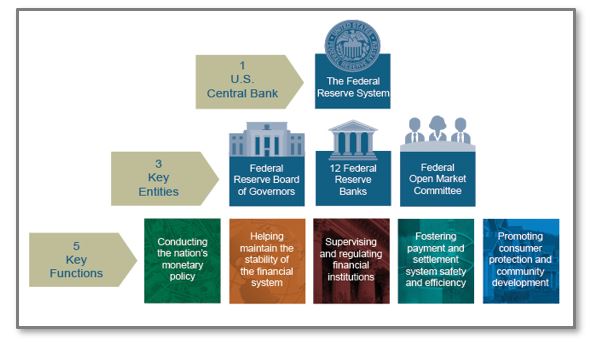

Since 2010, nearly 20,000 regulations have been pushed to banks and financial services institutions. While there were once more than 18,000 banks in the U.S., there are now fewer than 7,000 federally insured institutions nationwide. There are also around 7,000 credit unions which provide many of the same financial services as banks but are member-run and not-for-profit organizations. The relative size of financial institutions varies greatly and there are several regulatory agencies that oversee them including:

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (The Fed)

- Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC)

- National Credit Union Administration (NCUA)

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), part of the U.S. Department of Treasury7

For the American public, banking is an essential service. People adore their returns on investment and their ability to take out sizeable loans with questionable payback certainty. However, those same people are stricken with grief and malice during market downturns or technical errors that prevent them from accessing funds. It’s, in some ways, a very strange love and hate relationship. Regulatory becomes strong and empowered when the public reacts negatively but grows satiated when the government steps out of the game to allow our institutions the ability to internationally compete. Ultimately, the goal should be to achieve this “smart” status towards regulatory. This includes an empathetic understanding of when constrictions or guidelines are necessary and when they are not. If you do impose, how deep do the regulations cut and what sort of financial toll do you expect the institution to harbor to better meet the government’s expectations? It may be easier for a large-scale organization, such as JP Morgan, to adapt and manage regulatory change, but the fewer than 7,000 credit unions will have extensive difficulty meeting new directives and/or employing the critical and necessary staff needed in a timely/acceptable manner. Smart regulatory should include this broader scope of viewpoint – a strategy to not only view both sides of the coin but extract continuous feedback and collaboration amongst those impacted. As the Fed has done with tiering and potential earnings call scheduling changes, you must solicit these institutions’ opinion or stance and not purely draw conclusions from general populace voting. The intricacies and delicacies found within a financial service institution is one of complexity and innovation. Regulation can live side-by-side with this mentality – the smart way.

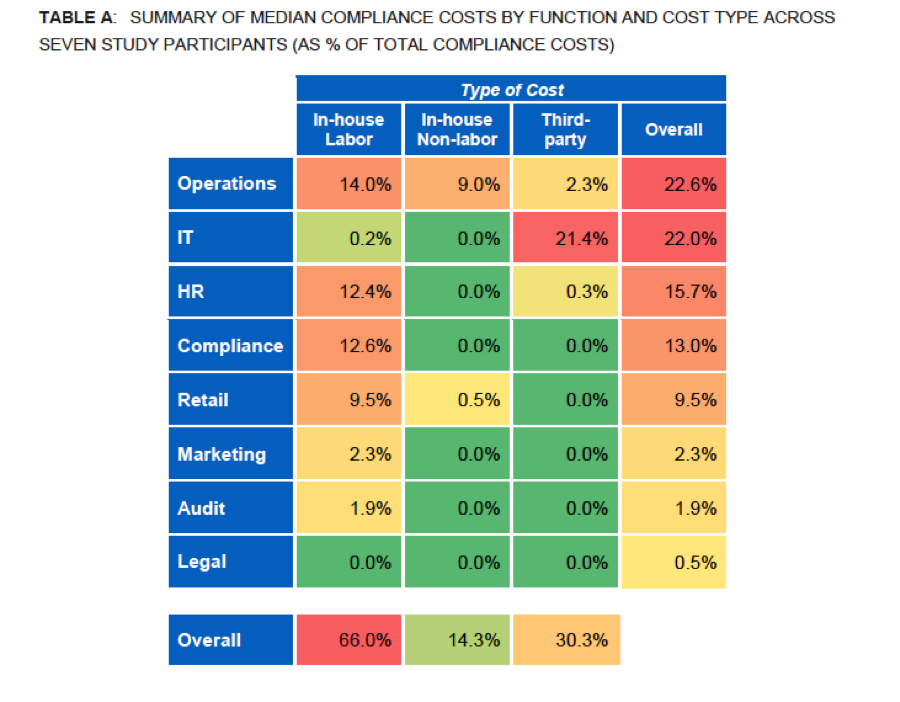

The below images represent a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau case study outlining deposit compliance costs and operational expenditures from 2013.8

References

[1] https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/tarullo20141107a.htm

[2] https://seekingalpha.com/news/3394835-second-tier-u-s-banks-may-ripe-get-back-m-wells-fargo-report

[3] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-18/sec-fulfills-trump-request-seeks-comment-on-quarterly-reporting

[4] https://www.nasdaq.com/article/editorial-should-us-companies-report-earnings-only-twice-a-year-cm1010910

[5] https://www.nasdaq.com/article/editorial-should-us-companies-report-earnings-only-twice-a-year-cm1010910

[6] https://www.thebowenlawgroup.com/blog/is-tiered-regulation-good-or-bad-for-banks

[7] https://www.thebowenlawgroup.com/blog/is-tiered-regulation-good-or-bad-for-banks

[8] https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201311_cfpb_report_findings-relative-costs.pdf